The Italian Constitution provides for the equality of all citizens as one of its fundamental values. The right to equality applies "without distinction of sex, race, language, religion, political opinions, personal and social conditions"1 and includes the access to equal opportunities and the possibility to fully participate in the political, social and economic life of the country. The Italian legal framework promoting gender equality is determined by the National Code of Equal Opportunities for Women and Men adopted in 2006.2 In 2020, the Ministry of Labour and Social Policies adopted the Three-Year Plan of Positive Action, which provides for specific measures to eliminate any forms of discrimination that could manifest themselves in different areas. The objectives include, among others, to guarantee equal opportunities in access to employment, in career development and professional training, as well as an improved organization of work and employment with a view to promoting work-life balance and, more generally, a culture aimed at respecting the principle of non-discrimination on the basis of gender.

Despite the notable progress made in promoting gender equality in the legal and policy framework, the measures taken for its implementation and the guarantees available in practice to ensure the equality of all citizens continue to face a number of serious challenges. The Global Gender Gap Report is ranking Italy 76th out of 153 countries in the world. It measures indicators related to the opportunities for participation in economic life, education, health and political engagement. In the European Union, the Gender Equality Index of the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) ranks Italy 14th, 4.4 points below the European average.

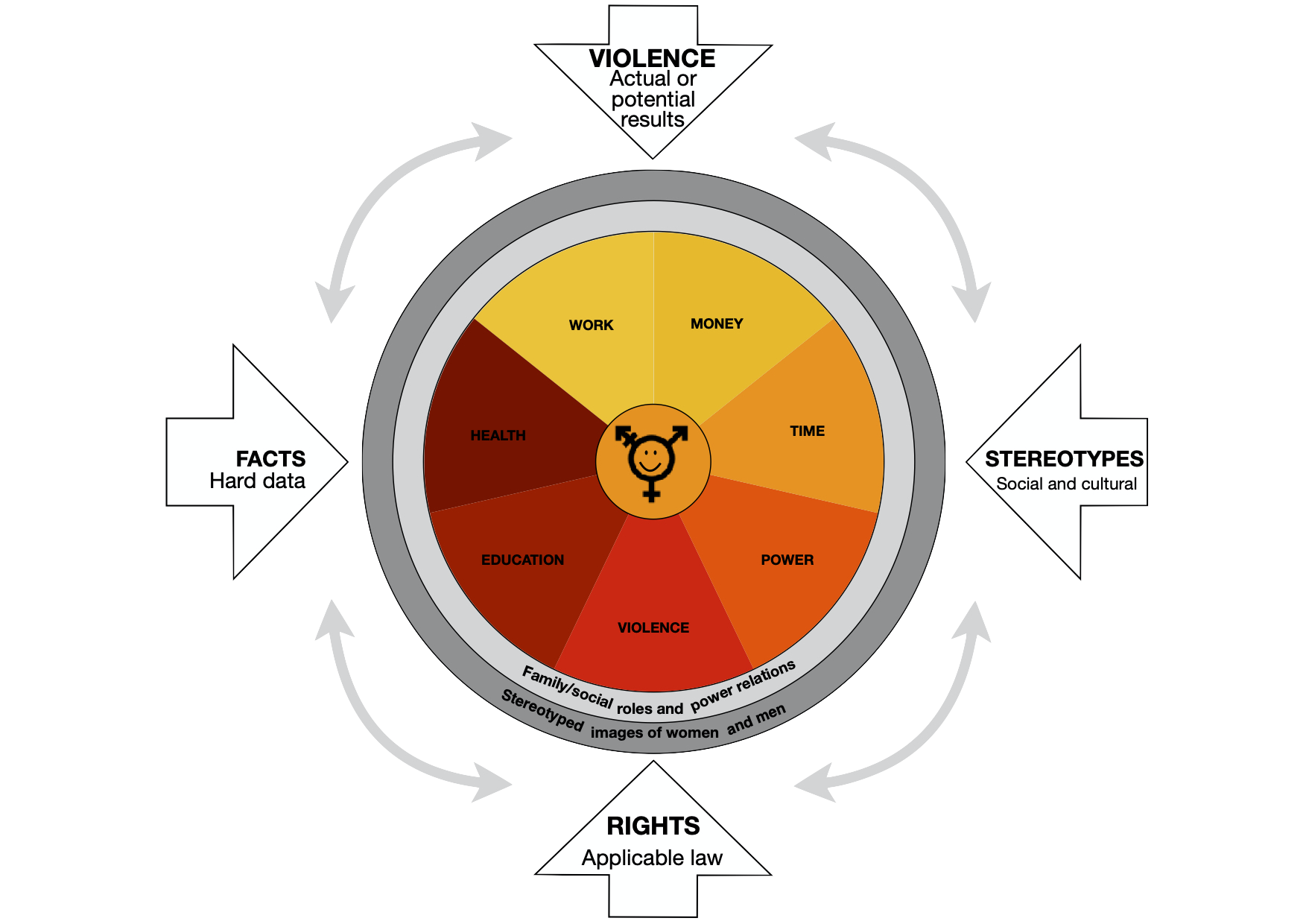

The Fairy Tales project adopted the EIGE indicators as a starting point for the reflection on how to address gender inequalities in activities with boys and girls (for further details, see section 3.1). We find it useful, therefore, to provide a brief overview of the legal standards and policies that have promoted gender equality in Italy and the progress made over the past years, specifically in light of these indicators. When developing the working methodology for this project, we referred to these indicators as "determinants".

The determinants relate to the following areas: work and employment; the availability of economic resources; participation in decision-making and the ability and power to influence these processes; health, which is understood as the overall well-being of the person; protection from all forms of violence; education and training, also in the context of professional training and personal development; leisure time available, taking into account the time used for domestic work and care as opposed to time spent with recreational, cultural and social activities.

In Italy, the equal opportunity policies started to develop with considerable delay compared to other European countries, mainly due to historical and cultural reasons. Despite the constitutional reform and the feminist movement for the emancipation of women, it was only at the beginning of the 1990s and upon the pressure exerted by the European Union that this sector started to evolve. Subsequently, the Italian normative framework has been gradually reformed to be in line with that of other European countries.

The 2019 EIGE report shows a considerable improvement with regard to the "gender gap" in the context of work and employment, an area where, despite the progress made, Italy remains on the lowest rank of all EU Member States. The legislative reforms made over the past 70 years have led to a continuous increase of women’s employment, in particular the increasing entitlements and guarantees for working mothers, a development that started as early as the 1950s. Law reform provided for, among others, protection from dismissal from the beginning of pregnancy through the child’s first year of life; a prohibition for employed pregnant women to transport or lift weights or to carry out work, which is otherwise dangerous, strenuous or unhealthy; and a prohibition for pregnant women to work during the last three months of pregnancy and for eight weeks after childbirth, whereas the time-frames can be expanded. In the 1960s, a number of laws were adopted that prohibited any type of dismissal of women in relation to marriage and provided for measures to support the maternity of agricultural workers.3 In the 1970s, the foundation for effective equality in employment was created by introducing a legal prohibition of discrimination in access to employment, vocational training, and income, as well as the recognition of professional qualifications and correlated salaries.4 In 2001, these and other laws and regulations were integrated in a single Act, which reorganized the legal regulations concerning the health of workers, maternity, paternity and parental leave, rest and annual leave, the care of sick children, seasonal and temporary work, home-based and domestic work, as well as the rules enjoyed by self-employed women and freelancers.5 European Union law on work and employment and its principle of equal opportunity have been transposed in Italian national law since the early 2000s.6

In addition to the developments in the normative framework, there are many other factors that have contributed to the steady increase in women's participation in the labour market over the past forty years: cultural changes, an increase in the level of education, the transition from an agricultural to an industrial and tertiary economy, a growing number of foreign women working in family services and, in recent years, also the tightening of pension eligibility requirements.7

Across Europe, including particularly in Italy, it is today still more difficult for women than for men to access employment, especially in high-level positions, leadership roles and positions with decision-making power. The so-called "glass ceiling" is still in place and difficult to break through.

With regard to the participation of all citizens in political and social life, the awareness of equal opportunities in this area started to grow only in the beginning of the 1990s. Italian women voted for the first time in 1946. Although Article 3 of the Constitution of the Italian Republic provides for the principle of formal and substantive gender equality, it was not until 1956 that women were admitted to certain careers in the judiciary.8 Women had previously been precluded from positions in the judiciary due to the assumption that an anatomical-physiological predisposition would allegedly make them unable to judge because they were victims of hysteria and irrationality.9 Only in 2003, however, when Article 51 of the Constitution was amended, women were granted the equal legal right to access employment in public offices and elected positions.

In the area of leisure time, the measures taken thus far have not yet succeeded to overcome the uneven distribution of family-related tasks and household chores among men and women. This continues to affect women’s work and employment in a negative way. The most recent data available from Italy confirm what has been reported at the international level.10 In our country, women in employment work 8 hours per week less in paid work, but 16 hours per week more in unpaid work compared to men. As a result, the weekly workload of employed women in Italy, including paid and unpaid work, amounts to more than 57 hours while that of men amounts to 50 hours or less.

With regard to the availability of economic resources, EIGE data from 2019 show that women earn on average 18% less than men do. Women continue to have less access to top management positions, are more likely to be employed in part-time jobs and have more frequent career breaks. These factors contribute to the gender gap in relation to income.

In the field of education, there has been a "gender overtaking": women study more, the majority of university graduates are female and statistically, women have better grades.11 In Italy, as well as in almost all European countries, the school dropout rate is lower among girls than among boys. Some studies have shown, however, that there is a "hidden curriculum" at school, i.e. a tendency towards educational segregation where female students are rather directed towards areas traditionally considered suitable for women, such as education and care, and male students towards scientific-technological subjects, thus reconfirming some of the typical stereotypes and expectations.12 These stereotype expectations are affirmed also within the schoolbooks used in primary school, which display predominantly male figures, as well as a stereotyped view of male and female professions and a language that uses an "undistinguished male".13 In order to overcome these critical issues, gender and sexual education should be systematically introduced in all school levels. Today, these subjects are still missing from the curricula despite the various Conventions ratified by Italy that would make it a requirement (in particular CEDAW and its Optional Protocol14 and the Istanbul Convention15). During the past years, there have been many attempts to introduce gender education in schools, but the relevant proposals have not been approved or are still pending. This is partly due to an anti-gender campaign, which has been particularly fierce, also at the political level16, and which was supported by anti-democratic movements of dubious origin.17

In 2015, following the school reform, the Italian Ministry of Education, Universities and Research developed a"National Plan for Education for Respect". The National Plan aimed to promote a culture of respect within schools that values differences and contrasts homophobia and gender-based violence. In spite of the numerous educational initiatives underway to address these aspects with children, the attention dedicated to these areas remains inadequate, which is not in compliance with the relevant legislation.

In relation to health, the EIGE presents a high score for Italy, unlike all the other domains examined. The analysis, however, does not consider aspects related to reproductive health, for instance, which would include sexual education at school. This was also noted by some of the participants in our courses.

Furthermore, if we consider the aspect of protection from violence, which is closely linked to health, while there have been concrete developments in recent years in the legal domain, the necessary measures have not been taken to ensure the effective implementation of these laws. In fact, gender-based violence does not appear to be decreasing in Italy: in 2018, 142 femicides were reported (an increase of 0.7% compared to the previous year), a large part of which were committed in the family.18

Italy has only recently introduced new laws to protect the person. In particular, rape and sexual assault are a new and single criminal offence, and sexual violence has become a crime against the personal freedom, whereas it used to be a crime against public morals and decency.

Italy has ratified the CEDAW and the Istanbul Convention, instruments that impose a specific obligation on States parties to remove any obstacles to women's effective enjoyment of their fundamental rights. Despite this progress and the various normative measures adopted in recent years, the CEDAW Committee has nevertheless reprimanded our country in relation to femicide, noting that "socio-cultural attitudes that condone domestic violence" persist in Italy.19 It is therefore a cultural problem that, on the one hand, legitimises discrimination based on gender, even among those who should act to change it, and on the other hand, prevents effective measures to protect women's rights and self-determination.

The recent report of the GREVIO20 highlights several critical issues related to budgetary appropriations, interagency coordination in responding to victims and the fragmentation of territorial services, and emphasises that the tendency to reinterpret and reorient the notion of gender equality in terms of family and maternity policies is a cause of concern.

The main obstacle to a smooth process towards gender equality is the persistence of a sexist and misogynistic culture of the Italian society at all levels. The patriarchal structure of the family is still part of Italy's cultural heritage, combined with the idea that the family has to be protected from external interference and threats that could compromise its "natural" composition. In addition, the traditional roles of men and women in the society continue to be defended and justified through a naturalistic discourse. Despite the notable progress made in the normative framework and culture, the historical traditional conception of the family considers the woman’s role confined to her function as the “angel of the hearth”, that is exclusively as bride and mother (and never a person as such). This view remains the lead argument of the anti-gender movements that consider the autonomy and emancipation of women a threat to the much-acclaimed traditional family. On the other side, paradoxically, the communication of some leading mass media, in particular television channels, discredits and denigrates women by representing them in a way that reduces women to bodies with sexual and seducing features.21

Up to the 1970s, the civil order remained strongly connected to the idea of a closed family unit, with an authoritarian father figure at the centre who has the power to command and correct his wife and children, who are considered uncontrolled by nature. The 1975 family law reform paved the way for a whole series of innovations. They included the introduction of divorce, the adoption of laws regulating abortion, the equality between men and women in the context of employment and positive action to remove the obstacles to such equality, as well as the elimination of jus corrigenda, that is the legal justification for the use of force and violence by the husband against his wife, for the alleged purpose of correction. Thanks to the impetus of European case law, the institution of marriage has also evolved. The Law on Civil Unions22 is a reform of historic proportions as regards the protection of fundamental civil rights, but also because of its cultural importance, which leads to a shift from the concept of "family" to that of "families": different and yet, today, all worthy of being protected within our system.

——————————————————————

1. Constitution of the Republic of Italy, Article 3.

2. Law 198/2006.

3. Law 7/1963, Prohibition of dismissal of female employees due to marriage and changes to the law of 26 August 1950, No. 860, “Physical and economic protection of motherhood in employment”.

4. Law 903/1977, “Equal treatment of men and women in the field of employment and occupation”.

5. Consolidation Act No. 151/2001 "Consolidation Act of the legislative provisions on the protection and support of motherhood and fatherhood”.

6. See in particular Law 215/2003 Transposition of the Directive 2000/43/EU implementing the principle of equal treatment between persons irrespective of racial or ethnic origin; Law 216/2003 Transposition of Directive 2000/78/EU establishing a general framework for equal treatment in employment and occupation; and Law 67/2006 “Measures for the judicial protection of people with disabilities who are victims of discrimination”.

7. Hearing of the President of the National Institute of Statistics Giorgio Alleva, “Constitutional Affairs” Commission of the Chamber of Deputies, Rome, 25 October 2017, accessed from https://www4.istat.it/it/files/2017/10/A-Audizione-parit%C3%A0-di-genere-25-ottobre_definitivo.pdf?title=Parit%C3%A0+tra+donne+e+uomini+-+26%2Fott%2F2017+-+Testo+integrale.pdf.

8. In fact, only with the Law of 27 December 1956 No. 1441 “Women's participation in the administration of justice in Jury Courts and Juvenile Courts”, women were allowed access to the judiciary, “albeit limited to the functions of popular (ordinary or substitute) judges and members of Juvenile Courts”.

9. L’evoluzione dell’immagine della donna nell’Italia degli anni Cinquanta: “Vie Nuove” e “Famiglia Cristiana”, Simona Zannoni, 2018.

10. ISTAT, 2019, I Tempi della Vita Quotidiana. Lavoro, Conciliazione, Parità di Genere e Benessere Soggettivo [The Times of Everyday Life. Work, Conciliation, Gender Equality and Subjective Wellbeing], accessed from https://www.istat.it/it/files//2019/05/ebook-I-tempi-della-vita-quotidiana.pdf.

11. https://www.istat.it/donne-uomini/bloc-2a.html?lang=it ma anche Euridice https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwjWucOditHpAhXF-aQKHaqxCosQFjABegQIARAB&url=http%3A%2F%2Feurydice.indire.it%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2017%2F06%2FGender_IT.pdf&usg=AOvVaw1BLVNnlqXxNsJsdJARdivF

12. Elisabetta Musi, 2015, A scuola di pari opportunità, Il sistema scolastico: un circuito decisivo – ma trascurato – per educare al rispetto dell’identità e della differenza di genere [A school of equal opportunities, The school system: a decisive - but neglected - circuit for education in respect of identity and gender differences].

13. Where the male gender is used to indicate the universality of people, automatically giving more centrality to the male gender. See: Pink is the new black, Stereotipi di genere nella scuola dell’infanzia - Abbatecola E., Stagi L., Rosenberg & Sellier 2017.

14. CEDAW Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women New York, 18 December 1979 ratified in Italy in 1985.

15. Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence, 11 May 2011, ratified by Italy in 2013

16. See: Marzano, M. (2015), Papà, mamma e gender [Dad, Mom and Gender], Novara: Utet.

17. See: Article by Siviero, G., Il Post, https://www.ilpost.it/giuliasiviero/2016/02/22/i-movimenti-no-gender-spiegati-bene/

18. Report “Femminicidio e violenza di genere in Italia” [“Femicide and Gender-based Violence in Italy”], 2019, La Banca Dati EURES https://www.eures.it/sintesi-femminicidio-e-violenza-di-genere-in-italia/

19. Concluding observations of the CEDAW Committee to the Government of Italy, 26/7/2011.

20. GREVIO is the independent expert body responsible for monitoring the implementation of the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (Istanbul Convention) by the Parties. The report is available from https://rm.coe.int/grevio-report-italy-first-baseline-evaluation/168099724e.

21. Documentary “Il corpo delle donne” (The women’s body) by L. Zanardo, available from http://www.ilcorpodelledonne.net/documentario/.

22. Law 76/2016.

Related Articles

The activities carried out, as described above, have generated an important opportunity to translate the challenging pedagogical…

The working group that carried out the project activities in Italy, which was tasked to address such complex and sensitive…

The first exploratory phase with children, teachers, and parents during spring 2019 allowed us to focus and refine the questions…

In light of the overall objectives of the project, the working methods were selected with due consideration to the joint…