Theoretical framework of reference

The working group that carried out the project activities in Italy, which was tasked to address such complex and sensitive issues as described above, raised a whole range of questions. The choice was not to simplify but, on the contrary, to enter the "forest" of issues that the project aimed to address, just as in a fairy tale.

For this purpose, the way in which Italo Calvino describes the nature of popular folkloristic narratives was helpful and inspiring:

|

"...fairy tales are real. Together, in their constantly repeated and constantly varied casuistry of human matters, they offer a general explanation of life, which was created in ancient times and preserved by the slow contemplation of the peasant consciousness up to us; they are a catalogue of the destinies of men and women, especially for that phase in life that is all about designing one’s destiny: youth, from birth that often carries within itself an aspiration or a condemnation, to the departure from home, the tests and trials to become an adult and then mature, in order to confirm for yourself that you are human. And in this summary drawing, there is everything: the drastic division of the living into kings and the poor, but their substantial equality; the persecution of the innocent and his rescue as the terms of a dialectic that is inherent in every life; the beloved one found before even knowing the person and then lost immediately, with suffering; the common fate of being under spells, that is to be determined by complex and unknown forces, and the effort to free oneself and becoming autonomous as an elementary duty, together with that of freeing others, indeed not being able to free oneself, but becoming free by liberating others; fidelity to a commitment and the purity of the heart as basic virtues that lead to salvation and triumph; beauty as a sign of grace, but which can be hidden under a robe of humble ugliness like that of a frog's body; and above all the unitary substance of everything, men beasts plants things, the infinite possibility of metamorphosis of what exists".1 |

The fairy tales, therefore, are not a simplified representation of reality but an engaging metaphorical convergence of symbols, diversity, social expectations, biographies and destinies of all human beings. This understanding certainly helped to consider the multiple dimensions of the narrative as an ideal context for a pedagogical reflection. It also offered the opportunity for this reflection to be transformed into an action that becomes meaningful for children and for adults, including those who led the project themselves. At the same time, the decision in favour of the complexity appeared to be the only one that could ensure a rich and meaningful educational path, useful to address the important themes at the heart of this project without trivializing issues that are still largely unresolved in the adult world.

The need to define and translate concepts in a way to be shared with 5-7 year old children was therefore an extraordinary opportunity to reconsider important issues that are all too often taken for granted even in advanced and critical discussions of the topics covered. The diversity, discrimination, stereotypes and the use of metaphor to propose different interpretations beyond strict disciplinary codes emerged as dimensions that required closer observation and renewed exploration in order to share a meaningful perspective with boys and girls, teachers and parents.

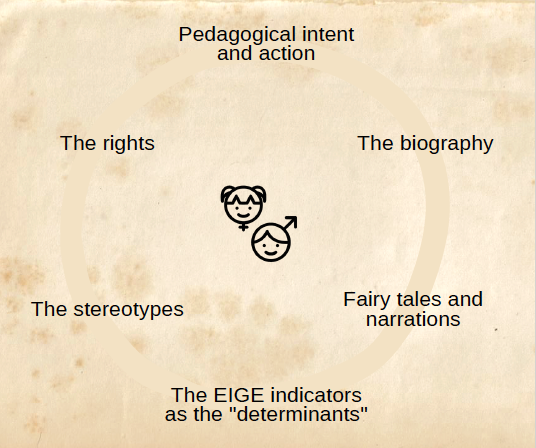

Perhaps influenced by the fantastic scope that fairy tales evoke, a sort of map was developed as the work progressed. It created a point of reference and orientation for the interaction with boys and girls and for the informative and educational relationship with the adults that were particularly important for the children.

Being aware of the project’s limitations in terms of time and modalities, as well as the infinite possibilities to address the key themes of the project from a multidisciplinary approach, this map was instrumental to guide the activities under the project. As every map is always different from the territory that it represents2, the ambition was certainly not to address the topics in an exhaustive manner or to develop a single model approach, but rather to propose a possible pathway that can be modified and improved in view of the experience made and the perspectives of those who embark on this journey, and to translate problems and challenges related to the topics covered into pedagogical practice.

Pedagogical intent and action

The project combined activities addressing the question of gender equality with the objective of engaging children and adults in an educational and self-educational experience.

The development of a comprehensive educational approach could not just involve the “translation” of already defined concepts and contents into technical and didactic methods. On the contrary, as the activities progressed along the project implementation, it became more and more clear that the issues at stake were calling for an in-depth pedagogical reflection and elaboration that could connect any proposal to the children, with the attempt to elaborate paths and responses, with a new approach that still had to be developed.

How would it have been possible to propose to children criteria on what is right and what is wrong with regard to questions of gender discrimination, without resorting to fictitious narratives? How would it have been possible to engage the children in a pedagogical exercise, without recognising that in contemporary reality, the ethical views of adults on these issues differ significantly from facts and behaviours? The fact-based reality is characterised by inequality that structurally involves all dimensions of social life, of the economy, of our history and with them our personal life stories. This simple observation led us to think and design the project activities in such a way as to create a context in which we could address fundamental issues, through a pedagogical approach, that would eventually have a meaning and relevance beyond our initiative.

In this sense, we can say that tackling diversity and gender discrimination has been a challenge not only in creating a useful path for boys and girls but, in particular, in reaffirming an educational process that succeeds to achieve a substantial civil, cultural and ethical engagement. This educational process aimed to target adults who are all confronted with these issues and the problems arising from them, from equal opportunities to gender-based violence.

If we want to understand pedagogy as the discipline dealing with the challenges of education, we have to be aware of and consider how the issues at stake are at the heart of the educational problem. Without recognising this critical challenge, the very reason for proposing activities of this nature to children is missing.

With regard to the project activities, therefore, a decision was taken to share with the boys and girls a series of problems that concern everyone and to engage them in an experience where they explore and interpret these issues in an interactive way without relying on predetermined responses.

This exercise was prepared in simple and sensitive terms, gradually progressing in accordance with the diversity of the individual learning processes of children in the age group targeted by the project. It aimed to take into consideration the different contexts and origins of each person. This approach corresponds to a central dimension of the project because it requires that the issues at stake be dealt with in an inclusive manner, avoiding stereotype and selective narratives that are not corresponding to reality. The overall objective of this approach was to avoid reproducing the chronic hypocrisy that often characterises the relationship between the world of childhood and the adult world.

Against this background, we can say that the intent and the educational action in relation to the issues at stake were essential and complemented each other. In the following sections of the report, we will illustrate how the project has attempted to translate the orientations described thus far into specific operational modalities.

Fairy tales and narration

The narration of oneself meets traditional narratives to interpret the world between the own and the collective story.

We have already discussed above how Calvino's “holistic” proposal prompted us to consider fairy tales in an open and positive way with regard to all the imaginable propositions that can derive from them. If it is true that elements of gender discrimination and other types of discrimination can be found in fairy tales, it is equally true that they offer a range of positive cues that provide useful inspiration for a reflection on equal opportunities and inclusion.

In this regard, and certainly in the awareness of all the many useful theories that analyse different aspects of popular narratives, the project preferred to use fairy tales as an opportunity to talk with children about fundamental questions. This should prepare them to gradually and sensitively approach and understand different matters related to the project, while still appreciating the fantastic and magical dimension of many narratives.

It is certainly true that fairy tales offer a good opportunity for talking with children about situations and cases that could not be addressed directly (as for instance the example of children abandoned by their parents, family violence, the imposition of marriage, the power of adults to the point of raw violence and femicide). It is precisely this characteristic that allows children to relate to the fairy tale, and which leaves room for the child to exercise his or her own narration, implicitly or explicitly, and allows us to engage even with adults to a significant degree of freedom of dialectical and philosophical discourse. The metaphorical dimension helps to create additional room for interpretation and for recognition, identification or distancing, which, if handled with sensitivity and attention to the multidimensional nature of learning processes, can generate important contexts for education.

In the specific context of the project, for instance, it was possible to create a realistic experience through dramatic structure and drawing, by dressing up as the one or the other, supported by the imaginary narration of the story, modifying in a natural way individual elements and outcomes of the original text.

It emerged therefore as an important aspect of the method not so much to process one fairy tale in order to tell then yet another, but rather to gently loosen up the fairy tale’s network so that new possibilities and new narratives could be generated that go beyond the original text.

In order to keep this possibility alive, an imaginary story was created (the story of the Monkey Island – see section 3.2) that encompasses, in a metaphorical way, the key issues to be shared with the boys and girls for them to explore the different traditional fairy tales. This approach was chosen in order to avoid an interpretation where the traditional fairy tale is confronted with a realistic and logical account. Instead, another metaphor was chosen that would allow the children to remain within the suggestive and stimulating place of the narration without imposing predetermined messages for the dialogical relationship that was to be developed during the sessions.

In the context of the project, the traditional fairy tales were used in their original versions, which is, in fact, very often radically different from the versions the children know from movies and television. The aim was to develop an approach and a methodology that could facilitate the interaction with the children also in relation to other types of narratives. The methodology, which will be described in detail in the following sections, had not been tested for other contexts, but it had purposefully been developed in such a way that it could also be used for other types of narration.

The biography

The sensitive relationship with the individual history of each person becomes instrumental for understanding the reality and for accessing the complexity of the world.

Is it possible to understand the phenomenon of discrimination and to interact with or on it, without considering our own actions and experiences with regard to discrimination in our life stories? This question guided the dialogue with the teachers in the preliminary phase of the project. The fairy tales, as a place where this can be recognised in an explicit, implicit or symbolic way, have thus become a particularly inspiring context to explore. It is possible to recognise traits of one’s own biographical story and narration, supported by each person’s sensitivity to the metaphorical dimension.

From the early stages of the project, we felt it was essential to address questions concerning gender discrimination as something that was closely related to the biography of each person but also to a collective biography.

In this sense, in addition to considering how the relationship between the key themes of the project and one’s own individual experience enabled a more extensive and substantial understanding, it became clear to us that, in the exchange with children, any direct or indirect interaction with them should always implicitly take their particular and unique life stories into account. In other words, we did not consider it feasible to propose a logic of what is “right or wrong”, except in the awareness that any message we shared with them could relate to the biographical contexts and origins of the children with whom we certainly could not interact in any direct way.

Once again, the metaphorical dimension allowed us to develop “third” contexts in a sensible way, supporting an educational potential that could be lived and shared by boys and girls, with due consideration to their own biographical-social-cultural contexts.

For us, this biographical dimension was the essential prerequisite and a safeguard for boys and girls to actively participate in the development of this experience. Through a mirror-like reflection, the biographical approach helped us to encourage the involvement of adults (service providers and teachers) and to enable them to expand the mere didactic activity and to enter into an interlocutory, interrogative, self-educational and circular dimension that we considered essential to establish a sincere and fruitful relationship with children.

The stereotypes

Prejudices are entrenching relations of power and subservience but they are also particularly important subjects and materials for pedagogical action.

We can consider the use of stereotypes as a constant dimension of our way of thinking, where we tend to rely on pre-determined concepts that are not necessarily well founded. The pedagogical question we posed was to consider the mechanisms through which we could succeed to consider our judgements and prejudices with regard to the surrounding reality with flexibility and openness. We decided therefore, not to “demonize” the stereotype as such but rather to understand its nature in order to allow us to disempower it and render it less rigid and inappropriate, with particular attention to gender stereotypes.

We therefore wanted to consider the stereotype as a collective narrative that is closely related with cultural dynamics, which often aim to consolidate relationships of power and subservience. When understood from this perspective, the stereotype can only be determined by real conditions and facts, which tend to express themselves in a common held view, and which, at the same time, reaffirm and reinforce precisely those conditions that determined it in the first place.

In the rationale that was made to prepare the pedagogical paradigm and framework of reference, we noted how, in the case of gender discrimination, the stereotypes within the fairy tales corresponded to historic facts and conditions in the relationship between the sexes and how many of these conditions together with the stereotypes that describe them are still relevant today. If in Snow White, the girl is fully occupied with domestic work, it is evident how this condition limits the opportunities of many women still today. This banal observation certainly lead us to consider the stereotype not as a fictitious narrative but as a deeply rooted structural narrative of today’s reality, which still determines the power relations between genders.

We considered then how important it was not to oppose the stereotype with another predetermined truth but that it was instead more appropriate, from the educational point of view, to attempt a possible deconstruction of prejudicial thought through an experience that could disempower the narrative by opening the weaving to other possibilities.

It is also important to note that the traditional fairy tales, unlike the more popular versions that children today are more familiar with and which have been reproduced for commercial purposes with a new interpretation, do promote gender stereotypes without, however, exhausting the wide range of potentials and capabilities attributable to one sex or another. In fact, in popular narratives, we find male and/or female characters who display different types of capabilities that are not necessarily attributable to their gender. An example is the determined solution-oriented capacity of Gretel, Hansel’s sister, in the fairy tale of the same name.

In the complexity of factors proposed by fairy tales, we considered it important not to focus so much on the most evident stereotypes proposed by the narration but much rather to identify the conditions that could help to overcome them. Snow White’s possibilities, for instance, to display not necessarily the actions attributable to the male characters of the fairy tale, but actions that could expand the range of her possibilities, considering that each individual, male or female, can express their personal identity when he or she faces the opportunities that allow him or her to do so.

From the pedagogical point of view, the aspiration was to exit, with the help of the metaphorical approach, from the rigid male-female opposition and all the specific roles and functions associated with one or the other, and to arrive instead at the category of the “individual”, who is always able to free him- or herself from the stereotypes that condition their existence, or to be liberated from them.

Human rights

The body of rights represents a multidisciplinary educational “logic” to be shared with children and adults.

We considered the body of rights an overall framework of reference for addressing gender discrimination and equal opportunities in a pedagogical way, despite the awareness of its distance from the actual reality of facts. In other words, we assumed that national and international law could legitimately represent the basic reference point for the development of a sound and solid pedagogical experience for children and teachers.

The “relativistic” view of the issues at stake, recognising the opportunity to express the own identity without any constraints imposed by cultural and social constructs, emerged precisely from the principles and norms deriving from the body of international human rights law, as a cultural heritage of humanity and therefore a basic reference point for any analysis and proposal aimed at guaranteeing the dignity and possibilities of every person.

We wanted to understand the normative framework as a synthesis and a platform on which to create a multidisciplinary perspective that could be translated into an educational paradigm. In this sense, and using metaphorical language to ease the relationship with the children, the intention was to progress from a logic based exclusively on the recognition of the child’s needs to an understanding where needs are connected and interrelated with the corresponding rights. From this perspective, the possibilities of a person result from the standards afforded under international human rights law and the supportive environment required to enable the person to exercise these rights.

Several treaties and conventions elaborate on the general principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights specifically in relation to gender issues, in particular the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). Together with an approach rooted in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), these instruments of international law have provided orientation for the horizon of values for the activities and guided the paths that we felt we could follow and translate, sometimes even explicitly, in our experience with children and teachers.

The story/metaphor of Monkey Island (see section 3.2) allowed us to represent, in a child-friendly way, and sensibly compared to the universe of the fairy tales that we were going to explore, a utopian world. This aimed at demonstrating a culture based on rights, understood as the basis of relationships between individuals and always respectful of each person’s possibility to express themselves and their stories.

The EIGE indicators as “determinants”

The effects of gender discrimination and the absence of equal opportunities become manifest, clearly and in a structural way, in all aspects of today’s world.

Speaking of gender discrimination and equal opportunities, we felt it was extremely important to link the issues addressed to a reality that is still a long way from full recognition of the law. While addressing the issue through metaphors and fairy tales, it would not have been possible to develop a pedagogical paradigm without considering the facts that around the world show a disparity between legal guarantees and actual treatment related to gender.

Against this background, as already discussed in section 2, we considered the EIGE indicators of gender equality as particularly useful in light of the approach chosen for the activities. The indicators could sustain a complex fact-based analysis that is helpful for teacher training and, at the same time, could be translated into areas and concepts that can be shared with children and guide the joint analysis of the narratives. We have thus proposed a series of “determinants” that reflect the EIGE indicators in order to address together with the children all the related dimensions of gender discrimination, including those of structural nature.

Work, money (in the workshops with children, this was translated in resources), knowledge, time, power, health and, in addition, the cross-cutting parameter of violence/protection, have thus become the foundation for the pedagogical proposal and the approach to dealing with stereotypes. Working with this approach requires us to recognise what has determined and continues to determine these dimensions.

The use of these “determinants” has made it possible to interact with the children without pushing them to engage in an open discourse that took on a particular meaning precisely because it was accompanied by fairy-tale metaphors. At the same time, the use of the EIGE indicators made it possible to synthesise the topics dealt with by proposing an additional simple map to guide the exploration of these complex themes.

——————————————————————

1. Calvino I. (1956), Fiabe italiane – Raccolta dalla tradizione popolare durante gli ultimi cento anni e trascritte in lingua dai vari dialetti [Italian fairy tales – Collection of popular tradition over the past hundred years and transcribed in Italian from the various dialects], Mondadori.

2. Korzybski A. (1994), Science and sanity: an introduction to non-Aristotelian systems and general semantics

Related Articles

The activities carried out, as described above, have generated an important opportunity to translate the challenging pedagogical…

The Italian Constitution provides for the equality of all citizens as one of its fundamental values. The right to equality…

The first exploratory phase with children, teachers, and parents during spring 2019 allowed us to focus and refine the questions…

In light of the overall objectives of the project, the working methods were selected with due consideration to the joint…